I was deep in the throes of coming of age when Francoise Sagan’s novel, A Certain Smile, hit the bestseller lists of 1956. According to a review in the San Francisco Examiner, “The reader is given the feeling of having opened a young girl’s diary by mistake. But whoever put such a diary down?” I couldn’t. With that younger woman/older man story, I began to see that, to the French, love is a game, a serious, high stakes, but survivable game. I minored in French in college, toured France at eighteen, and have been a sucker for French love stories ever since.

If you discount the existentialists, most French books are about the moves and feints in the game of love. Proust’s, In Search of Lost Time, is a study in unrequited love, suspicious love, duplicity in love. His love for Gilberte, later for Albertine, and the obsessions of the homosexual Charlus, are human, painful, silly, and never dull. His book reveals much of the era just before, during, and after WWI. Proust, a creature of his time, disguised his own homosexuality by making his two love interests women, but the romance remained gamesmanship to the max, displaying all the reversals, plotting, and focus of a chess match.

Modern French bestsellers include The Elegance of the Hedgehog, Muriel Barbary’s imagined love story is more gentle, mature, and less harried than Proust’s tumultuous upheavals. The dowdy concierge blossoms given the attention of a handsome, Japanese tenant. They begin the relationship by finishing each other’s quote from Tolstoy, “All happy families are alike. Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The romantic hero and heroine “see” each other and begin a slow, beautiful courtship. He wins the game by drawing her out.

Alex Caput is Swiss, but his novel, Leon and Louise, is supposedly the story of the love of his grandfather’s life. He approaches the game of love playfully. Our hero and heroine spar verbally, are frank with each other, and struggle to do the right thing after a terrible explosion and another man’s jealousy interfere with their lives. Like all the intellectual French, the narrator can’t resist philosophizing, but does it poetically. Here is an excerpt in which Leon finds women difficult to understand.

…he knew… a woman’s psyche is connected in some mysterious way with

peregrinations of the stars, the alternation of the tides and the cycles of the

female body; possibly, too, with subterranean volcanic flows, the flight paths

of migratory birds and the French state railway timetable—even, perhaps,

with the output of the Baku oil oilfields, the heart-rate of the Amazonian

hummingbirds and the songs of sperm whales beneath the Antarctic pack

ice.

Now, that, brings a certain smile.

I’ve always preferred novels’ endings, like good Scotch, served neat. No loose threads. No choices given the unsuspecting reader who thought all that was taken care of. I decided this some years ago when John Fowles wrote two endings to The French Lieutenant’s Woman, telling the reader to decide which to pick.

I’ve always preferred novels’ endings, like good Scotch, served neat. No loose threads. No choices given the unsuspecting reader who thought all that was taken care of. I decided this some years ago when John Fowles wrote two endings to The French Lieutenant’s Woman, telling the reader to decide which to pick.

When most of us think of bucket lists—that enumerated set of things to do before dying—we assume international trips, jumping out of airplanes, at the very least hot air balloon rides. There’s nothing wrong with such true adventures, but I have a parallel bucket list that emerged from my reading life.

When most of us think of bucket lists—that enumerated set of things to do before dying—we assume international trips, jumping out of airplanes, at the very least hot air balloon rides. There’s nothing wrong with such true adventures, but I have a parallel bucket list that emerged from my reading life. T.S. Eliot advises us that “April is the cruelest month,” because it mixes “Memory and desire.” True? For me, partly so. My winters have been spent in cold climates, and I love their cold sparkle and indoor coziness. A reader, I revel in the ritual of closing curtains at 5:00 p.m. against the dark, building up the fire, making tea, and opening a good book.

T.S. Eliot advises us that “April is the cruelest month,” because it mixes “Memory and desire.” True? For me, partly so. My winters have been spent in cold climates, and I love their cold sparkle and indoor coziness. A reader, I revel in the ritual of closing curtains at 5:00 p.m. against the dark, building up the fire, making tea, and opening a good book.

Flowers and gardens have always made me happy. So have stories set in them. Gardens, both vegetable and floral, have long been featured in children’s literature. B’rer Rabbit has to contend with the temptations of Mister McGregor’s cabbage patch. In Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant,” spring and summer depart from the grounds of a giant who builds a high wall to keep children from playing among his blooms and blossom-laden trees. Frances Hodsen Burnett’s classic The Secret Garden is all about discovery and the healing power of love and…gardens. Gardens are a tamed version of nature…with enough weeding and nurturing we do have dominion over them. But gardens are visited by wild creatures and the combination of beauty and natural life inspires our imaginations.

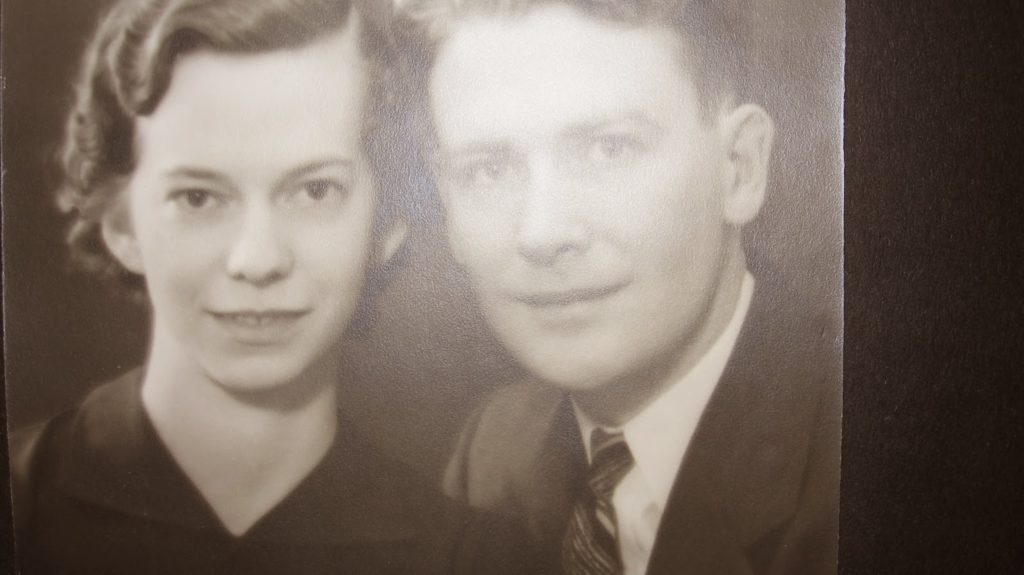

Flowers and gardens have always made me happy. So have stories set in them. Gardens, both vegetable and floral, have long been featured in children’s literature. B’rer Rabbit has to contend with the temptations of Mister McGregor’s cabbage patch. In Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant,” spring and summer depart from the grounds of a giant who builds a high wall to keep children from playing among his blooms and blossom-laden trees. Frances Hodsen Burnett’s classic The Secret Garden is all about discovery and the healing power of love and…gardens. Gardens are a tamed version of nature…with enough weeding and nurturing we do have dominion over them. But gardens are visited by wild creatures and the combination of beauty and natural life inspires our imaginations. I knew Mom kept letters she and Dad sent each other during WWII, but didn’t read them until a few years after her death. I think I wanted to prolong the anticipation, and felt a little uncomfortable looking at something so intimate and revealing about my parents. I knew theirs was a passionate marriage. How could something that started in a Montana town called Sunburst be otherwise?

I knew Mom kept letters she and Dad sent each other during WWII, but didn’t read them until a few years after her death. I think I wanted to prolong the anticipation, and felt a little uncomfortable looking at something so intimate and revealing about my parents. I knew theirs was a passionate marriage. How could something that started in a Montana town called Sunburst be otherwise?