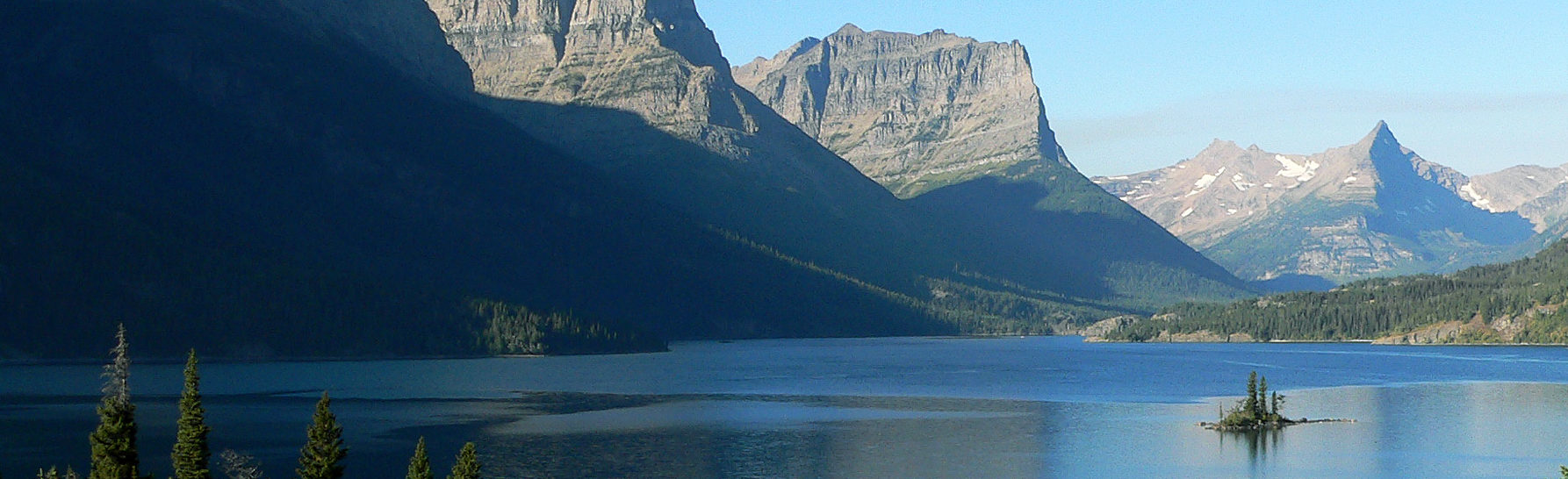

Flowers and gardens have always made me happy. So have stories set in them. Gardens, both vegetable and floral, have long been featured in children’s literature. B’rer Rabbit has to contend with the temptations of Mister McGregor’s cabbage patch. In Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant,” spring and summer depart from the grounds of a giant who builds a high wall to keep children from playing among his blooms and blossom-laden trees. Frances Hodsen Burnett’s classic The Secret Garden is all about discovery and the healing power of love and…gardens. Gardens are a tamed version of nature…with enough weeding and nurturing we do have dominion over them. But gardens are visited by wild creatures and the combination of beauty and natural life inspires our imaginations.

Flowers and gardens have always made me happy. So have stories set in them. Gardens, both vegetable and floral, have long been featured in children’s literature. B’rer Rabbit has to contend with the temptations of Mister McGregor’s cabbage patch. In Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant,” spring and summer depart from the grounds of a giant who builds a high wall to keep children from playing among his blooms and blossom-laden trees. Frances Hodsen Burnett’s classic The Secret Garden is all about discovery and the healing power of love and…gardens. Gardens are a tamed version of nature…with enough weeding and nurturing we do have dominion over them. But gardens are visited by wild creatures and the combination of beauty and natural life inspires our imaginations.

Adults seem to have a fondness for garden settings in their literature as well. What could be a more intriguing title for a novel than Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil? The recent bestseller,The Forgotten Garden, by Kate Morton is a grown up novel, obviously inspired by The Secret Garden. The garden in Morton’s book, if not able to heal all the characters’ ills, still brings comfort, peace, and literary inspiration.

There is mystery to these stories and books of gardens. We have to find the secret door, the hole in the wall, the place of entrance, then help the garden to flourish. No wonder we authors love gardens and garden stories. Entering the plot for a story we’re writing is like stepping into mysterious new worlds where the seeds of characters, themes, symbols, and subplots, are allowed to grow in the soil of our imaginations.

Our novels are our gardens.

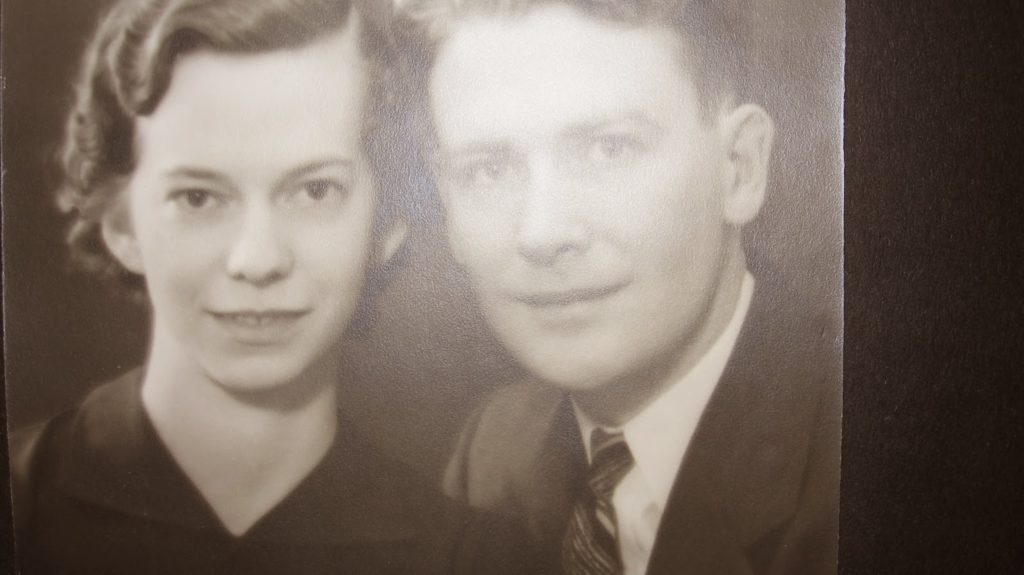

I knew Mom kept letters she and Dad sent each other during WWII, but didn’t read them until a few years after her death. I think I wanted to prolong the anticipation, and felt a little uncomfortable looking at something so intimate and revealing about my parents. I knew theirs was a passionate marriage. How could something that started in a Montana town called Sunburst be otherwise?

I knew Mom kept letters she and Dad sent each other during WWII, but didn’t read them until a few years after her death. I think I wanted to prolong the anticipation, and felt a little uncomfortable looking at something so intimate and revealing about my parents. I knew theirs was a passionate marriage. How could something that started in a Montana town called Sunburst be otherwise?