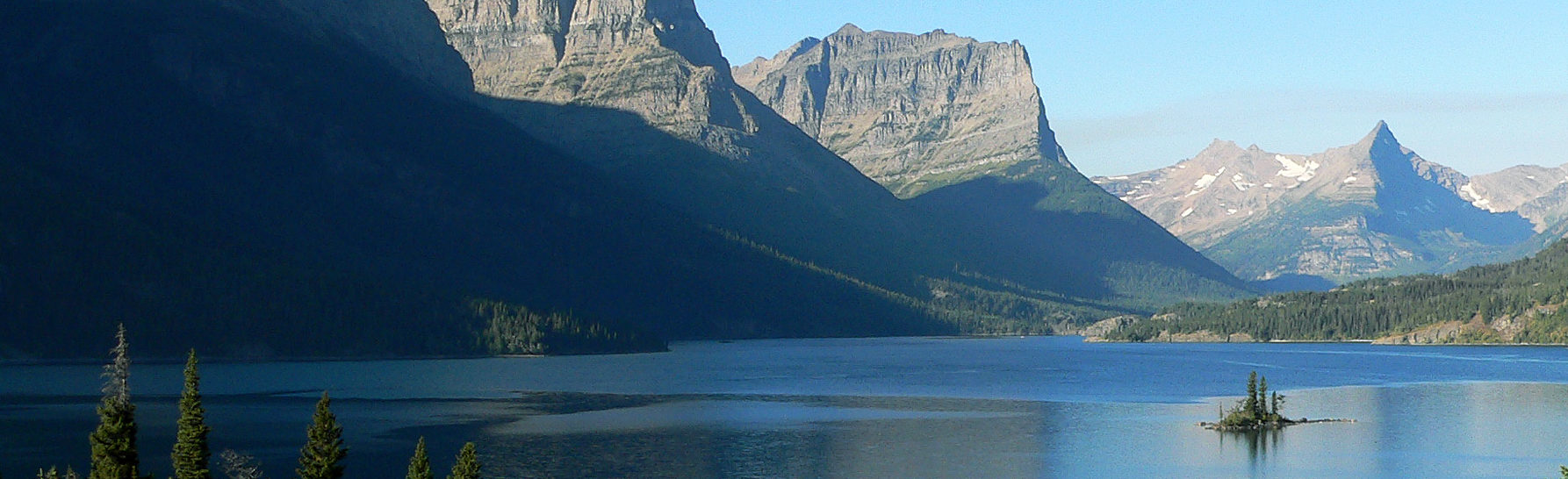

I’ve always loved snow. As a teen, I lived Joni Mitchell’s fantasy by actually having “a river I could skate away on.” Toboggans, snowmen, snow angels embodied the fun of winter for every child. As an adult, I’ve held on to that fun by cross-country skiing and tramping around on snowshoes in Glacier National Park. One of my favorite memories is a lovely “conversation” with two deer that appeared neither frightened nor surprised to see me.

But, snow is an equalizer with regard to more than recreation. It is beautiful, and beauty holds an element of mystery for observers. I’m always reminded of that when soundless veils of snow sweep from evergreens.

Poets and authors use snow’s transformative ability to show how it can test mere mortals. Jack London’s “To Build a Fire” is a cautionary tale about what happens to those who don’t respect nature in winter. The Indifferent Stars Above by Daniel James Brown, an account of the Donner party, conveys the same with horrors of cannibalism thrown in. James Meek’s novel, The Peoples’ Act of Love, includes the same taboo, but also makes snow symbolize the effects of the Russian Revolution which drove people to commit unspeakable acts to survive, or to rescue those they loved.

My favorite literary snowfalls come from Emily Dickenson and James Joyce. Dickinson acknowledges snow’s playful moods in “Snowflakes,” as well as its equalizing quality in her poem, “Snow.”

I’ll end with the close of Joyce’s story “The Dead.” The main character, whose wife has just told him she once loved a man who died, looks out on the snow-filled night, “…he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

Play in snow, appreciate its loveliness, but always respect its power and mystery.