“Nothing I force myself to write about ever turns out well, and so I’ve learned to wait for the voice, the incident, the image that reverberates.” Louise Erdrich

Erdrich is writing about more than titles, but that’s what I jumped to when I read her words. Have you noticed that some titles just reach out, make you want to explore the book, set off a little reverberating bell? Titles are so important. They’re meant to let us know a little about what’s in the book. That can be a person or place name. But they also have to have what Hemingway called magic. For me that means the words have to connote something, make us associate a word with implications and associations, for example, ‘Easter’ with spring and rebirth.

I’ve read that Hemingway searched the poetic King James Bible when he sought the right title for what became The Sun also Rises. Besides the Biblical source, the word ‘sun’ has strong connotations of light and warmth.

And, have you noticed that titles seem to have trends like fashion? That word ‘light’ has appeared in lots of titles lately. I think Anthony Doerr started with his wonderful, All the Light We cannot See. And ‘girl’. So many titles have that word. I think words float around and all at once catch us in our hearts, or intellects, or we associate them with other books. They work like magnets.

A friend who read a draft of my novel, Remarkable Silence, said the title was right there in the contents when a narrator commented that God remained “remarkably silent” on key matters. I wanted the word ‘river’ in the title of my novel, River with no Bridge that will be out this summer.

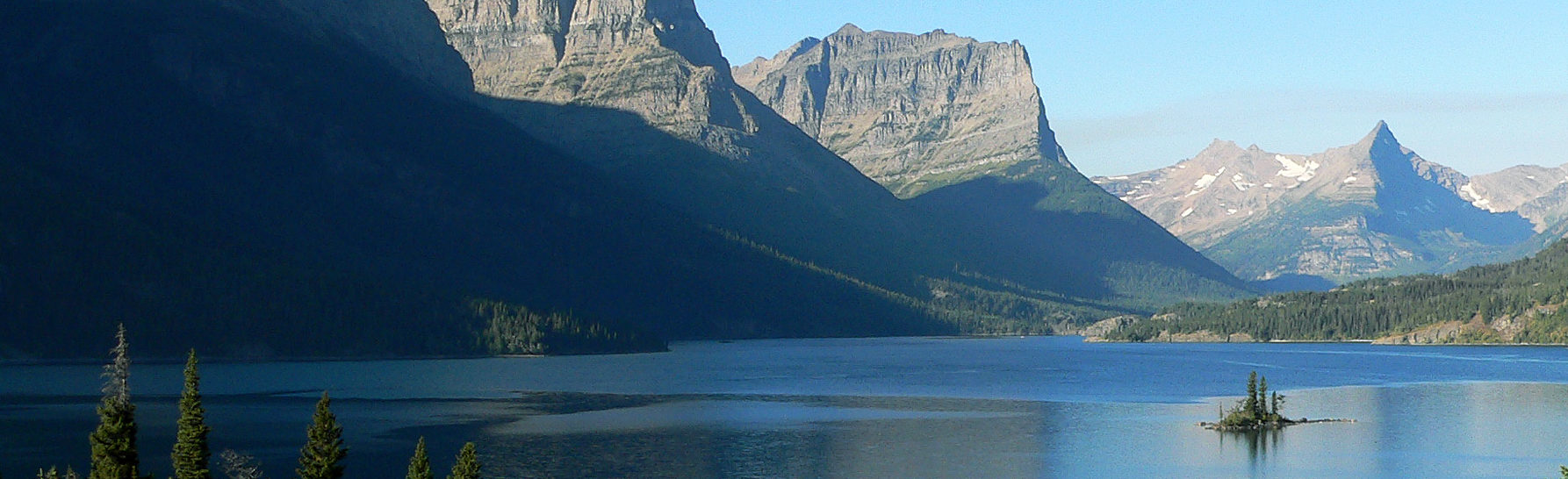

I wanted the word ‘river’ in the title of my novel, River with no Bridge that will be out this summer.  It’s another word with connotations of nature and crossings. The sequel I’m working on will be Garden in the Sky. That was the name of a popular campfire during the time of construction of the Going-to-the-Sun or Transcontinental Highway in Glacier National Park. The road figures in the story. I also think ‘Garden’ and ‘Sky’ have strong connotations.

It’s another word with connotations of nature and crossings. The sequel I’m working on will be Garden in the Sky. That was the name of a popular campfire during the time of construction of the Going-to-the-Sun or Transcontinental Highway in Glacier National Park. The road figures in the story. I also think ‘Garden’ and ‘Sky’ have strong connotations.

But I’m struggling for a title for a historical mystery I’ve just finished. Maybe I’ll just have to wait for something to reverberate. Luckily, Hemingway rejected both The World’s Room and They who get Shot before settling on the inspired, A Farewell to Arms. That must have resounded like a gong when the words finally appeared.

A sex scene should only be used as needed to move the story forward. The introduction of lovemaking changes characters’ relationships. A sex scene just to have a sex scene will never work. Authors often struggle with the verbal details of the sex scene. The words used can vary depending on the characters. Crude characters tend to use crude words. More refined lovers, and seducers, use a refined vocabulary. Writers also vary in our own ideas of propriety. Modern readers are quite sophisticated and unlikely to be as easily offended as their historical counterparts.

A sex scene should only be used as needed to move the story forward. The introduction of lovemaking changes characters’ relationships. A sex scene just to have a sex scene will never work. Authors often struggle with the verbal details of the sex scene. The words used can vary depending on the characters. Crude characters tend to use crude words. More refined lovers, and seducers, use a refined vocabulary. Writers also vary in our own ideas of propriety. Modern readers are quite sophisticated and unlikely to be as easily offended as their historical counterparts.